There’s a document called “Ma” on my desktop. I have been working on it since she was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s. Writing about it helps to get through some of the difficult days, an attempt to organize the messy unfolding of it all, an effort to put a puzzle together.

But the problem is that I can’t seem to finish it. Like her sentences, my written ones trail off to nothing. There seems to be no order to the paragraphs, no context to the lines of words. The puzzle is simply not coming together. In fact, it’s like I’m working from pieces from entirely different places.

I try, each time, to pan back, to create a framework and sum things up. I would really like to tick this box and file it, be done with it. Sort it. Get on with it. Get on from it. Yet, I continue, almost shamefully, to open and close it, throwing a few more incomplete phrases on top of the heap.

I’ve come to the conclusion that perhaps seeking order to this is not the way forward. Just like her speech, her words, her brain, things might simply need to stand half finished, upside down, scrambled. Grammatically wrong.

I’m going to take a page from her book, the one she lives daily, and search for the beauty in the chaos of the fragmented, hot, jumbled mess that just is. Something tells me it’s there, what I am looking for. Her.

Amica Residential Home.

It’s become familiar now, this strange transition, a crossing of a threshold from what feels like a real world outside, with its rushing cars, barking dogs and swaying trees, into another realm. While I haven’t been able to come to terms yet with my relationship to Amica, l know it to be a special place, for many reasons. One would never know as you drive by, what goes on inside this in-between kind of place. It’s own space, with its own job.

No, this isn’t the real world. It’s something else, somewhere else. A wonderland of so many things— hearts, bodies, wrinkled with age. Laughter, tears, the clanging of plates, the hum of scooters, doors softly opening and closing. Elevators going up and down. A few steps in, past the front desk and time slows. Minutes are carefully, graciously, elongated. A gift from the heavens.

But that’s not the whole picture. It houses my Mum and she expresses daily dislike for the place, as well as her failing brain. Magnus, her husband, aka her adjunct brain at the moment, cares for her patiently, diligently, day in and day out, minute by ticking minute, in a way that gives shape and form to the concept we call love. He does this while suffering with excruciating hip pain. Sometimes he screams into the empty air. The systems have failed him.

Yes, right now I feel very uncomfortable inside these walls. It feels heavy and I want to Uber back to the airport and fly away to my neat and tidy house where everything is in order.

“I like those shoes,” says one very old man to another as they sit side by side in chairs.

“Yah.” the other responds in a thick Canadian accent. “I bought them.” He says bluntly.

I listen, waiting for more about the shoes to emerge, but nothing else comes.

“What kind of mark are they?” his friend continues.

There’s no answer from the man with the shoes. He stares blankly in front of him. His friend doesn’t seem to mind. He sits there quietly.

I’m amazed at the kindness and attention to detail people offer one another in here, the gentleness with which they speak and listen. It feels similar to how very small children interact with one another. Slow and deliberate looks and touches. Wide eyes, careful observation. Little expectation. Soft. Some days its nice to be here in this other place.

I pass the front desk on the right and a bright sitting area that’s called the Bistro on my left. Toronto News is always on, with the volume up incredibly loud, but nobody watching. At times it’s dead empty, like at 8pm when everyone has gone to bed. But other times it’s very full of life, at 3pm Happy Hour or the collective birthday parties.

Taking ten more steps past the Bistro, I reach the elevator. Normally I have just enough wait time to look at the faces in the framed pictures that sit on a console across the hall. Sometimes there is just one, today there are two. I wonder where they have gone. What are they seeing, while we wait here for these doors to open.

Several of us shuffle into the elevator, one person behind a walker, another guided by a caregiver, delicately leading her companion by the elbow. The doors close and the sensation of my body being pulled upwards washes over me as I lean into a numbing quiet. We arrive at the second floor. You can’t see what’s there as there is a wall, but it’s always very silent. Eerily vacant. It’s nothing like the crazy fun and light laughter that spills from the 3rd and 4th floors. There’s a bit of madness in the air coming from those, the kind that makes you feel as if you are missing out on something when the elevator door closes and continues its journey upwards. Wait. Stop. What am I missing?

And anything above the seventh floor—well, we are all headed there.

I know, almost instinctually, when we reach the 6th. Walk out, turn left down the hallway. Room 603. The sound of my soft steps on a plush carpet.

A wreath of plastic fall flowers hangs from the unlocked door. I push it open, letting it click softly behind me.

I set down my bag, take off my shoes, and peer into the small suite. Cream walls, faded red Ikea couch. A coffee table I could spot a hundred miles away.

The wooden chair squeaks from the small office as Magnus turns to greet me. A little room crammed with so much–reminders of a life together as a couple, as well as ones they had before marrying. Pictures of his home town in Switzerland, his children, some here and others gone. A china cabinet too big for the space stuffed with books and papers and a small painting my daughter Isabelle had given to my Mum propped precariously on the edge, on top of some mail.

“How is she?” I ask.

“She woke up very angry this morning. Angry at the world. So she just went back to bed,” he says.

“Ok,” I say. Accepting. Sort of.

“Let’s not wake her.”

I pass the big brown trunk. On top of it sits a small stuffed dog in a little cushion bed. A string of shiny purple mardis gras beads have been draped haphazardly around its neck. She saw the dog in the window of one of her favorite shops on Main Street. You can put batteries in it so it breathes yet his have long stopped working. At the time I hadn’t understood why she had wanted it.

It’s a fake dog Mum. You have a real life.

Now, a couple of years later, I look at him with deep and longing respect. While I live thousands of miles across an ocean, he keeps a patient vigil, watching over her each and every day as she slips in and out of the life she once knew. I pat his head and run my hand down the length of his body, straightening the beads neatly around his neck. I swear I can feel his small body breathing.

“Good morning Doggie.”

I peer at the champagne glasses next to the sink from yesterday evening. We always drink Prosecco when I come. To celebrate.

The sound of children laughing and screeching hums in the distance from the schoolyard next door. I take in the familiar scene of a Canadian playground— concrete, snow and a bright blue sky. Memories of bitter cold mornings float through my mind. We called it Canada Cold, and only another Canadian would truly know what you were talking about if you said it. We would chase one another around the icy school yard daring one another to touch the flag pole with our tongues. Whoever did would be stuck there until the a teacher came out with hot water to painfully release it.

Since moving into Amica the sound of these children has been one of the few things my Mum admits enjoying. I catch her at times as she gazes at the children. She can look empty at first, but then a flicker, and you can tell she’s in her memories. Comforted, I wonder whether they are mingling with mine. A thread still connecting us.

I sink into the couch and wait patiently for her to appear from her bedroom. Our planned activity for the morning is to shower and wash her hair. I silently hope that with a bit more sleep she might have more life in her later— a few more steps in our walk, a few more chuckles in our chats.

The air is heavy and very warm, hot almost. The clock ticks harshly on the silent background. It’s ten in the morning but feels like two am. My heart rate slows, all internal gears down shift to what feels like a near stop. A faint wave of nausea washes over me–part jet lag, part disbelief. I rest my head on an aztec printed pillow and close my eyes, longing to escape, like I did as a child, cuddled up on the couch with her watching over me.

Sinking, I let go, being pulled, sucked into the thick arms of sleep.

It’s a long time ago. I am crouched in a closet, aged three or maybe five, scared because I am sure someone is in the house. I can’t find my mum anywhere and I’m frightened. It is a dreadful feeling, not being able to find her. Panic.

Reality. A decade later I look for her again, in the aisle of the grocery store. But she’s gone. Disappeared into a new life. When I visit her in their apartment in Toronto, I look for her there too, in her eyes. Sometimes I found her, other times not.

But here she is. Next to me, as I give my newborns their first sponge baths over the kitchen sink. And she’s here again, by my side in Nanchang, China, as we wait on the bed in a musty hotel room for Isabelle to be delivered to us from the orphanage.

A thought sails through my mind. Looking for Mum. Finding Mum. She’s here, she’s there, she’s neither. Rock solid and elusive at the same time. Now with Alzhiemer’s, it feels like an equal dance of both. Yes, it’s been a theme, the plot of our movie, together in this life.

I struggle to open my heavy eye lids. I see her tender body, crouched and fragile, appear from the opening of her room. She holds onto the frame of the door and looks into the room, confused, her hair slightly disheveled. It reminds me of how my own children, as they woke from their naps, hung in the daze of another world. Her eyes lock onto me. It takes her a moment to focus, perhaps to realize who it is, then a faint smile spreads across her face as she makes her way, carefully across the room. She stands confused in front of the couch, not knowing what to do.

“Mum. sit down” I say, pulling her next to me and kissing her head. I tuck her neatly under my arm.

I watch as the water from the shower spills over her head. It looks smaller to me now wet. Maybe it shrank. I feel like I am towering over her little body, her rounded shoulders. She grabs the soap and turns to face the water, cringing like it’s hurting her. I check the temperature and it’s perfectly warm. She looks into her hands at the bar of soap like its a foreign object, then to me with a worried look. She stares deep into my eyes and begins to cry, heaping heaving tears fall from her sweet, face. Lost. Aware.

“You poor thing” she says clearly. “You must be…” It trails.

“I’m just fine Mama. Don’t worry. Let’s get your face done, that’s it…and under your arms.”

I’ve made the list on the airplane. To Do with Mum. I underline it as if I might forget. But how could I.

-

- Get nails done

- Sort clothes – (wash the dirty pink sweater)

- Have 2 lunches out

- 1 dinner out

- Walk on the Bruce Trail

It’s very predictable. The lunches.

At The Shepherd’s Crook Pub she will order a Guinness and a bowl of soup. At Heather’s Bakery, she’ll pick gingerly at an egg salad sandwich and sip half a glass of water. This was where she would frequent with her girl friends. Both died. Too early. Neither reaching sixty. She was devastated each time. Heart. Broken.

We’ll cross the street to The Way We Were, her favorite consignment store. She will gaze at the rows of clothes like they are from another time, another era, another planet. Then she will run her hand down the seam of a skirt with the precision of a seamstress.

This is the way it will all go.

Nails. She does not like the nail lady at the mall anymore and is scared to go see her. I crouch at her feet and set her hands on her knees. We inspect together. “Hmm” she says giggling. “Not good,” she continues sheepishly. Her nails are usually perfectly done. Today they are chipped. We had gone to the drug store and carefully picked out the bright red color she only wears and a clear top coat. Best quality only. Fumbling around the bathroom cabinet to find the nail polish remover, I come across at least two new bottles of each, neatly stored.

I begin to rub the old polish off from her nails. They are the most beautiful, strong nails you will ever see. She’s forever running a finger up and around her tips, scanning for the slightest cuticle or rough spot on the polish. She might have lost the thread of her thoughts, but not the seamless length of her rounded nails. I spend ages applying each coat until I think they will pass the test. I sit back, pleased with my work, sad it’s over.

“Mum wait. They need to dry.” I say.

Magnus appears, ready for his lunch. She looks at him and gets up obediently, unbuttoning her pants, ruining her nails in the process.

Mum. no. your nails aren’t done. you aren’t in the bathroom. wait. where did our time go? I hide my thoughts in my brain.

“It’s ok Mum, we’ll redo them later. Let’s get you to the loo.”

It’s a beautiful day and I long to take her on the Bruce Trail, a walking route she cherished when she lived in their home in Limehouse. She worked long hours in busy downtown Toronto as an executive assistant to the head of Bell Canada, the leading telecoms company in the country, arranging important things like his private jets to meetings with the Prime Minister.

The trail and her garden were where she reconnected with herself and the simplicity so innate in her. Each time we visit, my sister and I make sure we get her feet back on those wooded paths, so she can seek the comfort she always had from the trees, the rushing stream and the fresh air.

I park the car next to the church and town hall, excited to get her OUT. She so rarely leaves the suite nowadays.

I struggle to unlatch her from the belt. When I finally do, we both take a deep breath like we have completed something incredibly monumental. Then she is very nervous as she attempts to get a foot to reach the ground. Once she does she has to trust me to pull her up. I can see a look of sheer terror come across her face as if I was asking her to walk a tight rope a thousand miles from the ground.

Today we have the crisp crunch of new fallen snow under our feet and the clear Canadian blue sky stretching out as far as we can see.

“You see things like that” – she points to something. I scan where she is looking and try to grasp what it is that she is noticing, but the sentence ends abruptly before I can find the thread.

“Do you remember the one that used to…?” I wait for more. It doesn’t come.

“What was that Mum?”

“I don’t know.” she says.

“I don’t think I can.. oh ” she begins to wander off the path.

“Where are you going Mum? Let’s stay on the trail, “ I say, guiding her back.

She has her own language, but if you pay careful attention you can follow the crumbs. I look for her in her words, trying to find her. Sometimes I do and we both know it. It’s lovely when that happens and normally we laugh. Over what, neither of us knows. It doesn’t matter.

She is unsteady on her feet, with the roots and rocks and the snow. It’s all a foreign place today. But we finally get down to the bridge and she turns to face the stream, sparkling in the winter light. She sniffs the air and breathes deeply. Something in her resonates. remembering.

“I’m in there somewhere.” she states. Clear as fucking day.

Watching Call the Midwife on Netflix is her favorite thing to do now. It’s about a group of nurse midwives and nuns working in the East End of London in the late 1950s and 1960s who visit expectant mothers, providing women the care they need in desperate times. My Mum might sleep most of the day yet after dinner she will binge watch the series, chuckling warmly. You can feel the comfort she is getting from the birth of babies, the strength of women. War time London. Things she knows. A place she is from. While she has always said that England was no longer her home, I don’t believe her. I can’t hear the show myself as she has her head phones in but I can feel her.

Hi Mum, I see you. You are there.

She always lit candles. Every night. I spend at least an hour at Walmart smelling all of the candles over and over to pick the right one, the perfect scent for her, even knowing she can’t smell anymore. It just might comfort her. I settle on one and it makes my day. Excited, I drive the slushy streets back to Amica, place it on the coffee table, and futz about looking for a lighter.

“That’s very nice Lydia but it will set the fire alarm off,” says Magnus. “We can’t have candles here.”

I’m ruined. I set it under the fake little Christmas tree. Lid on.

There she is again— next to me in a cycle rickshaw in India and we are laughing as we fly into the Delhi traffic.

Five years ago. I am with my sister and my Mum in Saint Remy de Provence for a little girly get away. We have finished our dessert and are getting the bill. Mum picks up a piece of bread and begins to spread left over whipped cream on it.

Twelve years ago. Morocco. The whole family has gathered for my 40th birthday. We are in the courtyard of and ancient Riad. This is where I saw the darkness in her eyes for the first time. Where have you gone?

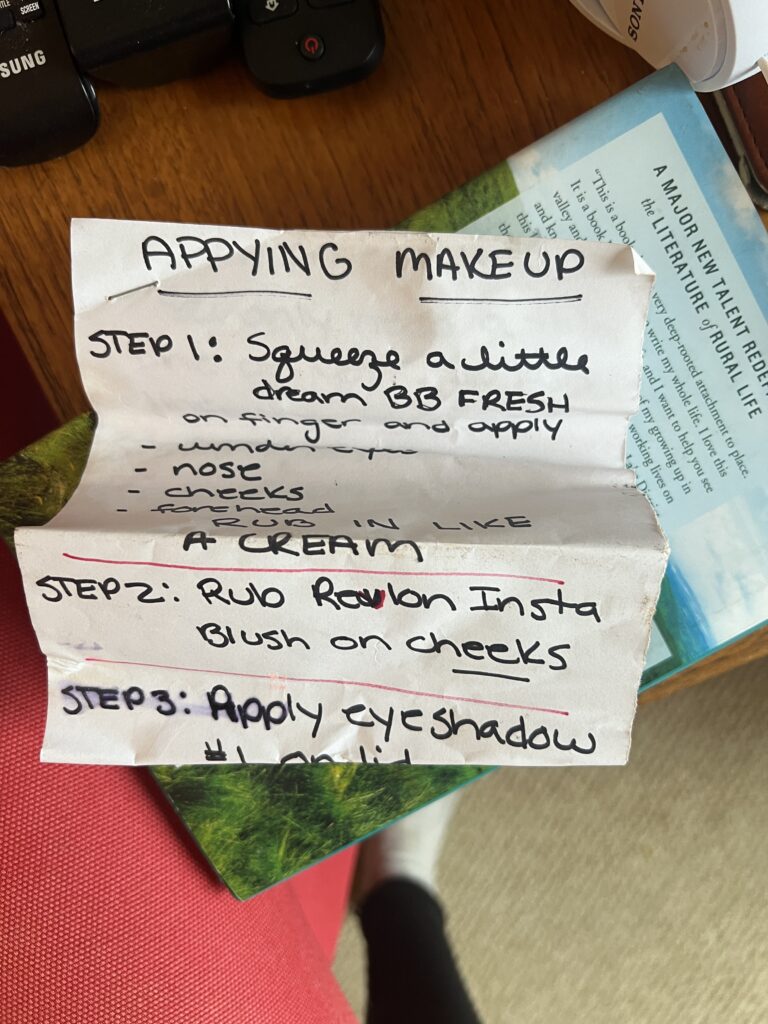

Her little makeup bag stays in the same spot in her dresser where my sister left it with a note she wrote 3 years ago giving her instructions on how to apply it. Nobody tells you that you might be teaching your mother how to apply lipstick later in life.

Her little makeup bag stays in the same spot in her dresser where my sister left it with a note she wrote 3 years ago giving her instructions on how to apply it. Nobody tells you that you might be teaching your mother how to apply lipstick later in life.

Sometime in 2022, or was it 2021, I planted sunflowers in my vegetable patch. My Mum always had these tall giants in her house, which was really more like a cottage in the countryside on the outskirts of Toronto. I was amazed by the way these flowers presided over her garden, though I can’t say I particularly liked them. They aren’t soft and dainty like the ones I am drawn to, but I had a certain respect for them, most of all because she loved them. So I planted them in my garden, wanting to feel my Mum’s presence in my growing space.

That first year they were spectacular, growing in between the white oleander that lined the patch, swaying steadily even in the strong mistral winds.

When the season as over, slowly, they tipped their heads towards the ground. It was a transition I will never forget the first time I experienced it. Here they were, these proud and sturdy beings that had faced their sun loyally and fully each and every day, yet little by little, as if honoring the earth itself from where they came, bowed, their heads, then died.

In the moment there was something so tragic about it. How could a plant so vibrant, so alive, wither so quickly. I refused to accept it as the end. I cut each head from their thick stalks and held them in my hands. In that moment they felt heavy and complete, and my sadness shifted.

I put them in a basket and trudged them over to the terrace where I could sit and see the sunset. Turning them over I was overwhelmed to discover just how many seeds were held in one round face. Hundreds, maybe more. Too many to count. All from one single being of a sun flower.

I let them dry a little more in the end of summer sun, then removed the seeds carefully to plant again the following spring. I pulled some extra aside, placing them in a bowl in the courtyard for the birds to snack on.

Despite her deteriorating condition, my Mum made the trip over to my home in Europe that summer. I tried to keep her busy with tasks that I knew were second nature to her– ironing, snipping flowers or hanging the wash on the line, something I will forever associate with her. Even in the coldest of winter mornings in Canada, you could find her putting her clothes on the line in her backyard. Mum they will never dry I would say doubtfully, every time I saw her trudge out in her winter boots.

“They will, you will see– the sun does its job, even in the cold,” she would say firmly. And it did. It might have taken a day, maybe two, but she would return with a heavy basket of folded clothes, fresh and dry from the winter sun, grinning ear to ear.

Now with me and my wash line, she struggles with the first wooden pin, but she soon finds her rhythm. I know she is truly in a groove when she rehangs what I have put up, making sure that the pins are placed evenly at the tips of my linen napkins. After the two lines are full with swaying fabric, she stands back and inspects her work. Yes–she seems to be saying to herself. Yes that will do.

Knowing deep down that this might be the last time she will be in my home, I savor every minute of our wash-hanging time together. Each movement, from basket to line, is cherished.

Every time I walk out to do the same, alone, after she left, I can feel her with me. I make sure to shake out the wrinkles and pin the corners of my napkins neatly.

There is a little small square of earth that the masons had left when they were redoing the courtyard, next to the wash line. After my Mum left, I noticed a small green sprout growing there. I was going to pull it, thinking it was a weed, but something stopped me. Even in seedling form, it had a strength and dignity that I knew to be more interesting than a common weed.

So I let it grow, inspecting it each time I went to line. I almost fell over the day I identified its sweet green head to be a baby sunflower. Of all flowers to have taken root by my line. Maybe it blew in from bowl I had left for the birds. It continued to grow over the coming weeks, watching over as I tended to my flapping sheets in the summer breeze.

Hi Mum. I’m finding you everywhere.

in my vegetable garden

in the smell of baking

in my tea cup

in your old pink diary

in mine

in the breeze of a warm day

in laughter

Hi Mum. I’ve Found You.